Chapter 2 Manifolds

2.1 Topological Manifolds

Definition 2.1 Let \((M,\mathcal{T})\) be a topological space with topology \(\mathcal{T}\). Then \(M\) is called an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold, if the following holds:

- (TM1): \(M\) is Hausdorff.

- (TM2): The topology of \(M\) has a countable basis.

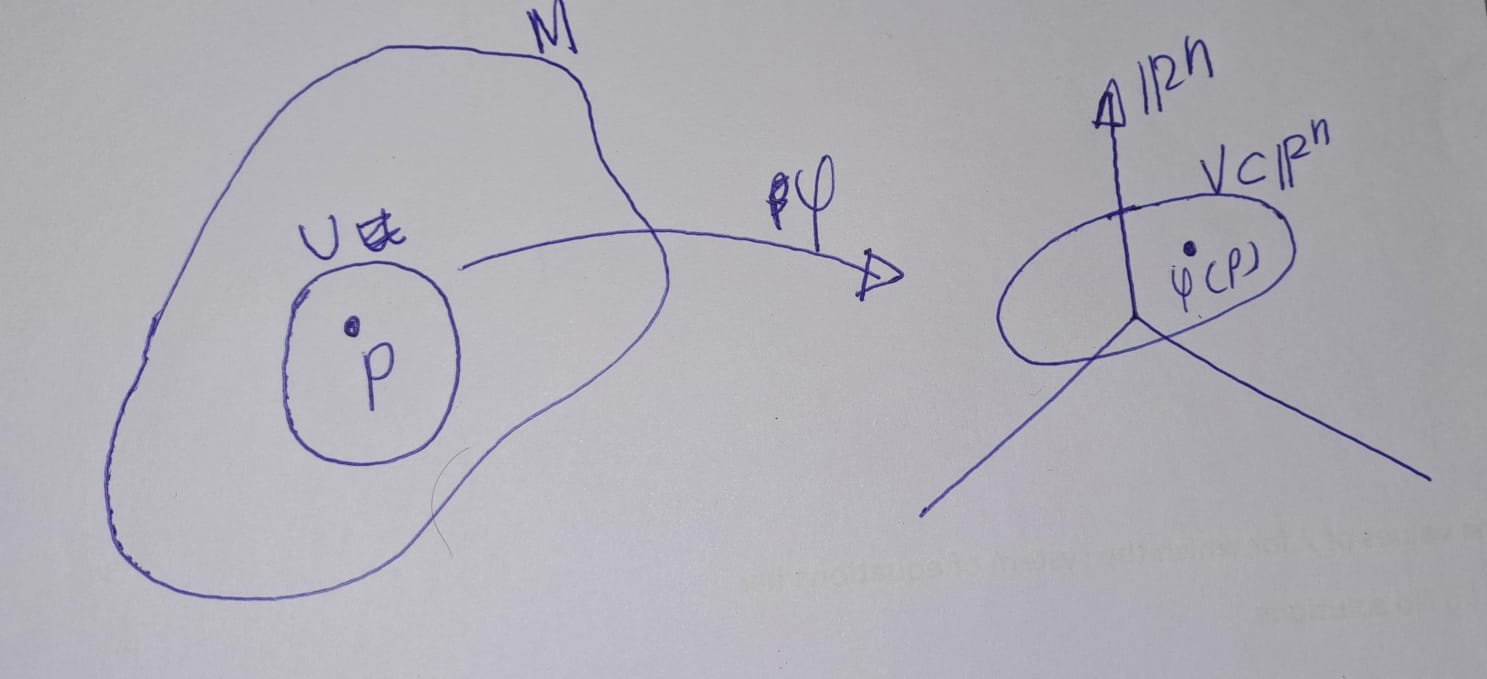

- (TM3): \(M\) is locally homeomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^n\), that is, for all \(p \in M\) exists an open subset \(U \subset M\) with \(p \in U\), an open subset \(V \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) and a homeomorphism \(\varphi : U \rightarrow V\).

Figure 2.1: \(~\)

Remark. The first two conditions in the definition 2.1 are more of a technical nature and are sometimes neglected. The important fact is that a topological manifold is locally homeomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Loosely speaking, manifolds look locally like Euclidean space. If the topology on \(M\) is induced by a metric, then the first condition is satisfied automatically. If \(M\) is given as a subset of \(\mathbb{R}^N\) with the subset topology, then both conditions M1 and M2 are satisfied automatically.

Let’s see some examples.

Example 2.1 Euclidean space \(M=\mathbb{R}^n\) itself is an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold:

- (TM1): We know that \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is metrc space. Let’s say the metric as \(d\). Let \(x,y\in \mathbb{R}^n\) with \(x\neq y\). Let \(r=d(x,y)\). Since \(x\neq y\),\(r>0\). Let \(U_x=B(x,r/2)\) and \(U_y=B(y,r/2)\). So, \(x\in U_x\) and \(y\in U_y\) We need to show that \(U_x \cap U_y\neq \emptyset\). We are going to proof by contrdiction. So, asssume the contray, there exist \(z\in U_x\cap U_y\). Thus, \(d(x,z)<r/2\) and \(d(y,z)<r/2\). Then, \[r=d(x,y)\leq d(x,z)+d(z,y)=d(x,z)+d(y,z)<\frac{r}{2}+\frac{r}{2}=r\] This is contradiction. Hence \(U_x\cap U_y \neq \emptyset\). Therefore \(M=\mathbb{R}^n\) is Hausdorff.

- (TM2): Later I will update this part

Problem :(.

- (TM3): Let \(U=\mathbb{R}^n=M\) and \(V=\mathbb{R}^n\) and \(\varphi=id\). We can easily tell that idenntity map is bijective. Furthur, we can observe that inverse of identity map is itself and it is well defined. So, Let \(U'\subset U=\mathbb{R}^n\) be an open set \[\forall x\in U'\quad id^{-1}(x)=id(x)=x\]. Thus, \[id(U')=id^{-1}(U')=U'.\] Hence, by definition of continuous mapping, \(id\) and \(id^{-}\) are continuous.

Example 2.2 Let \(M \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) be an open subset. Then \(M\) is an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold.

(TM1), (TM2) Obvious.

(TM3) Holds true with \(U = M\), \(V = M\) and \(x = \text{id}\).

Here Ia m not going to proove this. It is very similar to first example.

Example 2.3 The standard sphere \(M = S^n = \{ \underline{y}=(y^0,,.,y^{n}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1} : ||\underline{y}|| = 1 \}\) is an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold.

- (TM1) and (TM2) , since \(S^n\) is a subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{n+1}\).

- (TM3) We construct two homeomorphisms with the help of the stereographic projection. Let \(N\) be north pole of the n-sphere, that is \((\underbrace{0,,.,0}_{n~times},1)\in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}\). Let \(U_1:=S^n\setminus \{N\}\) and \(v_1=\mathbb{R}^{n+1}\). We define

\[\begin{eqnarray}

\varphi:U_1&\to & V_1\\

\underline{y} =(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n) & \mapsto & \frac{(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)}{1-y^{n+1}}

\end{eqnarray}\]

- Cliam 1: \(varphi\) is injective.

Let \((x^0,,.,x^{n}),(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)\in \mathbb{R}^n\). Suppose that \(\varphi(x^0,,.,x^{n})=\varphi(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)\).

\[\begin{eqnarray}

\varphi(x^0,,.,x^{n})&=&\varphi(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)\\

\frac{(x^0,x^1,,.,x^n)}{1-x^{n+1}}&=&\frac{(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)}{1-y^{n+1}}\\

(y^0, y^1, ,., y^n)(1-x^{n+1}) &=& (x^0, x^1, ,., x^n)(1-y^{n+1})\\

(y^0 - y^0x^{n+1}, y^1 - y^1x^{n+1}, ,., y^n - y^nx^{n+1}) &=& (x^0 - x^0y^{n+1}, x^1 - x^1y^{n+1}, ,., x^n - x^ny^{n+1})\\

y^0(1 - x^{n+1}), y^1(1 - x^{n+1}), ,., y^n (1- y^nx^{n+1}) &=& x^0(1-y^{n+1}), x^1(1 - y^{n+1}), ,., x^n (1- y^{n+1})\\

\end{eqnarray}\]

Thus, \(y^i(1 - x^{n+1}) = x^i(1 -y^{n+1})\) for all \(i = 0, 1, ,., n\).

Since \(1 - y^{n+1}, 1 - x^{n+1} > 0\),

?

?

?

?

Problem HOW INJECTIVITY COMES:(.

CHECK:(.

- Claim 2: \(\varphi\) is surejctive.

Surjectivity means that for every \(\underline{v} \in V_1 = \mathbb{R}^n\), there exists some \(\underline{y} \in U_1\) such that \(\varphi(\underline{y}) = \underline{v}\).

So, let \(\underline{v} = (v^0, v^1, ,., v^n) \in V_1\). We need to find \(\underline{y} = (y^0, y^1, ,., y^n) \in U_1\) such that

\[\frac{(y^0, y^1, ,., y^n)}{1-y^{n+1}} = \underline{v}.\]

We can solve this equation for \(\underline{y}\) as follows:

\[\underline{y} = (1-y^{n+1})\underline{v} = \underline{v} - y^{n+1}\underline{v}.\]

We know that \(\underline{y} \in U_1 = S^n \setminus \{N\}\), so \(y^{n+1} = 1 - \|\underline{y}\|^2\). Substituting this into the equation gives us

\[\underline{y} = \underline{v} - (1 - \|\underline{y}\|^2)\underline{v} = \|\underline{y}\|^2\underline{v}.\]

Solving this equation for \(\|\underline{y}\|^2\) gives us

\[\|\underline{y}\|^2 = \frac{\|\underline{v}\|^2}{1 + \|\underline{v}\|^2}.\]

Substituting this back into the equation for \(\underline{y}\) gives us

\[\underline{y} = \frac{\underline{v}}{1 + \|\underline{v}\|^2}.\]

This is a well-defined point in \(U_1\) for every \(\underline{v} \in V_1\), so \(\varphi\) is surjective.

- Claim: \(\varphi\) is continuous.

Note that the inverse map \(\phi\) is given by, \[\begin{eqnarray} \phi : V_1 &\rightarrow & U_1\\ \underline{x}= (x^0, x^1, ,. , x^n) &\mapsto & \frac{(x^0,x^1,,.,x^{n-1})}{1 + x^n} \end{eqnarray}\] I will update this proof. I want some to to write rigirs proof:(.

Analogously, we define the homeomorphism, which omits the south pole: Let now \(U_2 := S^n \setminus \{S\}\) with \(S := ( 0,,. , 0, -1) \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}\) and \(V_2 := \mathbb{R}^n\). Then \[\begin{eqnarray} \varphi : U_2 &\rightarrow & V_2,\\ \underline{y}= (y^0, y^1, ,. , y^n) &\mapsto & \frac{(y^0,y^1,,.,y^n)}{1 + y^n} \end{eqnarray}\]

Therefore, \(n\)-sphere \(S^n\) is an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold.

Example 2.4 (Non-Example) We consider \(M := \{ (y^1, y^2, y^3) \in \mathbb{R}^3 | (y^1)^2 = (y^2)^2 + (y^3)^2 \}\), the double cone.

Since \(M \subset \mathbb{R}^3\), both (i) and (ii) are satisfied.

But \(M\) is not a 2-dimensional manifold. Assume it were, then there would exist an open subset \(U \subset M\) with \(0 \in U\), an open subset \(V \subset \mathbb{R}^2\) and a homeomorphism \(\varphi : U \rightarrow V\) with \(\varphi(0) = 0\). How do we Gruntee that such hormouphsim exsist that maps 0 to 0:( Without losss of generality assume \(V = B_r(x(0))\) with \(r > 0\). Choose \((p^1,p^2,p^3), (q^1,q^2,q^3) \in U\) with \(p^1 > 0\) and \(q^1 < 0\). Furthermore, choose a continuous path \(c : [0, 1] \rightarrow V\) with \(c(0) = x(q_1)\), \(c(1) = x(q_2)\) and \(c(t) \neq x(0)\) for all \(t \in [0, 1]\).

Define the continuous path \(\tilde{c} := x^{-1} \circ c : [0, 1] \rightarrow U\). Then \(\tilde{c}(0) = q_1\), \(\tilde{c}(1) = q_2\), that is, we have \(\tilde{c}_1(0) > 0\) while \(\tilde{c}_1(1) < 0\). Applying the mean value theorem we find, that there exists a \(t \in (0, 1)\) with \(\tilde{c}_1(t) = 0\). Then \(\tilde{c}(t) = (0, 0, 0)\) and consequently \(c(t) = x(\tilde{c}(t)) = x(0)\), which contradicts the choice of \(c\). Hence, \(M\) is not a 2-dimensional topological manifold.

Definition 2.2 (charts) If \(M\) is an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold, the homeomorphisms \(\varphi : U \to V\) are called charts (or local coordinate systems) of \(M\).

Figure 2.2: \(~\)

After choosing a local coordinate system \(\varphi : U \rightarrow V\) every point \(p \in U\) is uniquely characterized by its coordinates \((\varphi^1(p), \ldots , \varphi^n(p))\).

Example 2.5 (0-dimesional manifold) In a \(0\)-dimensional manifold \(M\) every point \(p \in M\) has an open neighborhood \(U\), which is homeomorphic to \(R^0 = \{0\}\). Consequently \(\{p\} = U\) is an open subset of \(M\) for all \(p \in M\), that is, \(M\) carries the discrete topology. Since there exists a countable basis for the topology on \(M\) and the topology is discrete in addition, \(M\) has to be countable itself.

Figure 2.3: \(~\)

Proposition 2.1 A topological space \(M\) is a 0-dimensional topological manifold, if and only if \(M\) is countable and carries the discrete topology.

Proof.

(\(\implies\)) By definition, a 0-dimensional topological manifold is a topological space where every point has a neighborhood homeomorphic to the 0-dimensional Euclidean space, which is a single point \(\{0\}\). This implies that for every point \(p \in M\), there exists an open neighborhood \(U\) such that \(\{p\} = U\). This is exactly the definition of a discrete topology.

Since, there exists a countable basis for the topology on \(M\), and every point in \(M\) is an open set (i.e., the topology is discrete), then \(M\) must be countable. This is because every point in \(M\) corresponds to an open set in the basis, and since the basis is countable, \(M\) must also be countable.

(\(\Longleftarrow\)) If \(M\) carries the discrete topology, then every subset of \(M\) is open. In particular, for every point \(p \in M\), the set \(\{p\}\) is an open set. This means that every point in \(M\) has a neighborhood homeomorphic to the 0-dimensional Euclidean space, which is a single point \(\{0\}\). This is exactly the definition of a 0-dimensional topological manifold.

If \(M\) is countable, then there exists a countable basis for the topology on \(M\). Since every point in \(M\) is an open set (i.e., the topology is discrete), this basis can be taken to be the set of all singletons \(\{p\}\), where \(p \in M\).

Therefore, a topological space \(M\) is a 0-dimensional topological manifold if and only if \(M\) is countable and carries the discrete topology.

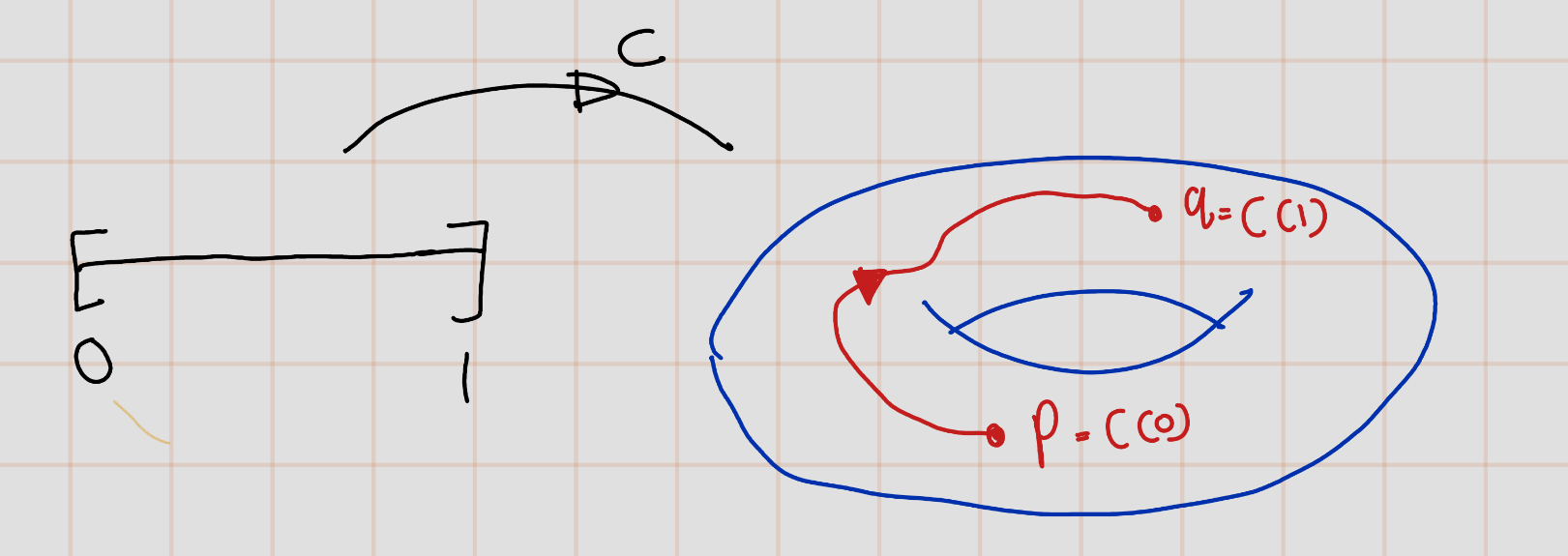

Definition 2.3 A topological manifold \(M\) is said to be connected, if for every two points \(p, q \in M\) there exists a continuous map \(c : [0, 1] \to M\) with \(c(0) = p\) and \(c(1) = q\).

Figure 2.4: \(~\)

Given two points, there has to be a continuous curve in \(M\) which connects both. Usually, in Topology one calls this path-connected, which is in the case of manifolds equivalent to being connected. We do not want to go deeper into this subject at this point.

Remark. Following Proposition every connected 0-dimensional manifold \(M\) is given by a single point: \(M = \{\text{point}\}\)

Proof. Let \(M\) be 0-dimesional connected manifold. Then by proposition2.1 \(M\) carries the discreate topology. Let \(p,q\) be distinct points. (i.e. \(p\neq q\)). Since \(M\) is connected that there exist continuous map \(c:[0,1]\to M\) such that \(c(0)=p\) and \(c(1)=q\).

Let \(U=c^{-1}(\{p\})\). Since \(\{p\}\) is open in \(M\) under discreate toplogy and \(c\) is continuous, \(U\) is open in \([0,1]\) under subspace topology.

Note that \(M\setminus \{p\}\) is sub set of \(M\). So, that is open under discreate topology. Since, \(c\) is continuous, \(V=c^{-1}(M\setminus \{p\})\) is open in \([0,1]\) under subspace topology.

Claim 1: \(V \cap U = \emptyset\)

\[\begin{eqnarray} V \cap U &=& c^{-1}(M\setminus \{p\}) \bigcap c^{-1}(\{p\})\\ &=& c^{-1}(M\setminus \{p\} \cap \{p\}~~(\text{by Claim 3})\\ &=& c^{-1}(\emptyset)~~(\text{by Claim 4})\\ &=& \emptyset \end{eqnarray}\]Claim 2: \(V \cup U = [0,1]\)

\[\begin{eqnarray} V \cup U &=& c^{-1}(M\setminus \{p\}) \bigcup c^{-1}(\{p\})\\ &=& c^{-1}(M\setminus \{p\} \cup \{p\}~~(\text{by Claim 5})\\ &=& c^{-1}(M)\\ &=& [0,1] ~~(\text{by Claim 6}) \end{eqnarray}\]Claim 3: \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)= c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\)

- subclaim 3.1 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Let \(y\in c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\). Then, \(c(y)\in U_1\cap U_2\). Thus, \(c(y)\in U_1\) and \(c(y)\in U_2\). So, \(\in c^{-1}(U_1)\) and \(y\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). Thus, \(y \in c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\). Therefore, \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\). - subclaim 3.2 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\supseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Let \(x\in c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\). Then, \(x \in c^{-1}(U_1)\) and \(x\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). Thus, \(c(x)\in U_1\) and \(c(x)\in U_2\). So, \(x\in c^{-1}(U_1)\) and \(x\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). \(c(x)\in U_1\cap U_2\). Therefore, \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\supseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\). Therfore \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)= c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\).

- subclaim 3.1 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cap U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cap c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Claim 4: \(c^{-1}(\emptyset)=\emptyset\).

Assume the contray, \(c^{-1}(\emptyset)\neq \emptyset\). Then we can choose that \(x\in c^{-1}(\emptyset)\). Thus, \(c(x)\in\emptyset\). This is a contardiction. Therefore, \(c^{-1}(\emptyset)\)Claim 5: \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)= c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\).

- subclaim 5.1 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Let \(y\in c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\). Then, \(c(y)\in U_1\cup U_2\). Thus, \(c(y)\in U_1\) or \(c(y)\in U_2\). So, \(\in c^{-1}(U_1)\) or \(y\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). Thus, \(y \in c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\). Therefore, \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\). - subclaim 5.2 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\supseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Let \(x\in c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\). Then, \(x \in c^{-1}(U_1)\) or \(x\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). Thus, \(c(x)\in U_1\) or \(c(x)\in U_2\). So, \(x\in c^{-1}(U_1)\) or \(x\in c^{-1}(U_2)\). \(c(x)\in U_1\cup U_2\). Therefore, \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\supseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\). Therfore \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)= c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\).

- subclaim 5.1 : \(c^{-1}(U_1\cup U_2)\subseteq c^{-1}(U_1)\cup c^{-1}(U_2)\)

Claim 6: If \(c:[0,1]\to M\) be continuous map such that \(c(0)=p,c(1)=q\), then \([0,1]=c^{-1}(M)\)\ Recall the definition of pre image of \(M\). \[c^{-1}(M):=\{x\in M | c(x)\in M\}\]

Subclaim 6.1: \([0,1]\subseteq c^{-1}(M)\).

Let \(a\in [0,1]\). Then \(c(a)\in M\). Thus, \(a\in c^{-1}(M)\). Hence, \([0,1]\subseteq c^{-1}(M)\). Thus, \(a\in c^{-1}(M)\).Subcliam 6.2: \([0,1]\supseteq c^{-1}(M)\).

Let \(b\in c^{-1}(M)\). So, \([0,1]\subseteq c^{-1}(M)\). Thus, \(b\in c^{-1}(M)\). Hence \(c(b)\in M\). Thus, \(b\in [0,1]\).

Claim 7 : \(V\neq \emptyset\).

Since \(p\neq q\) and \(q=c(1)\), then \(1\not\in c^{-1}(\{p\})=U\). Thus, \(1\in V=[0,1]\setminus U\). Therefore, \(V\neq \emptyset\).Claim 8: \([0,1]\) is connected.

We are going to use proof by contradiction. Suppose that \(A,B\) is a separation of \([0,1]\). Let \(a \in A\), \(b \in B\). Without loss of generality, suppose that \(a < b\). Since \(a, b \in [0,1]\), and \([0,1]\) is an interval, \([a,b] \subseteq [0,1]\). Let \(A' = A \cap [a,b]\) and \(B' = B \cap [a,b]\).Then, \[\begin{align*} A' \cup B' &= (A \cap [a,b]) \cup (B \cap [a,b]) \\ &= (A \cup B) \cap [a,b] \quad \text{(Intersection Distributes over Union)} \\ &= [a,b] \quad \text{(Intersection with Subset is Subset)} \end{align*}\] By the definition of a separation, both \(A\) and \(B\) are closed in \([0,1]\). Hence by Closed Set in Topological Subspace, \(A'\) and \(B'\) are also closed in \([a,b]\). From Closed Set in Topological Subspace: Corollary, \(A'\) and \(B'\) are closed in \(\mathbb{R}\). Now, since \(B' \neq \emptyset\), and \(B\) is bounded below (by, for example, \(a\)), by the Continuum Property \(b' := \inf(B')\) exists, and \(b' \geq a\). We have that \(B'\) is closed in \(\mathbb{R}\). Hence from Closure of Real Interval is Closed Real Interval, \(b' \in B'\). Since \(a \in A'\) and \(A \cap B = \emptyset\), it follows that \(b' > a\). Now let \(A'' = A' \cap [a,b']\). Using the same argument as for \(B'\), we have that \(a'' = \sup(A'')\) exists, that \(a'' \in A''\) and also \(a'' < b'\). Now \((a'',b') \cap A' = \emptyset\) or \(a''\) would not be an upper bound for \(A''\). Similarly, \((a'',b') \cap B' = \emptyset\) or \(b'\) would not be a lower bound for \(B''\). Thus, \((a'',b') \cap (A' \cup B') = \emptyset\). But since \(a < a'' < b' < b\), we also have \((a'',b') \subseteq [a,b]\), and \((a'',b')\) is non-empty. So, there is an element \(z \in (a'',b')\), and hence in \([a,b]\), which is not in \(A' \cup B'\). This contradicts (1) above, which says that we have \(A' \cup B' = [a,b]\). From this contradiction it follows that there can be no such separation \(A \mid B\) on the interval \([0,1]\). Therefore, by definition, \([0,1]\) is connected.

By claim 1,2 and 7, \(U,V\) are separation of \([0,1]\). This is contartract the the connectedness of \([0,1]\) interval.

Proposition 2.2 Every connected \(1\)-dimensional topological manifold is homeomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}\) or to \(S^1\).

Proof. Hard

The only compact,connected topological manifold of dimension \(1\) is \(S^1\)

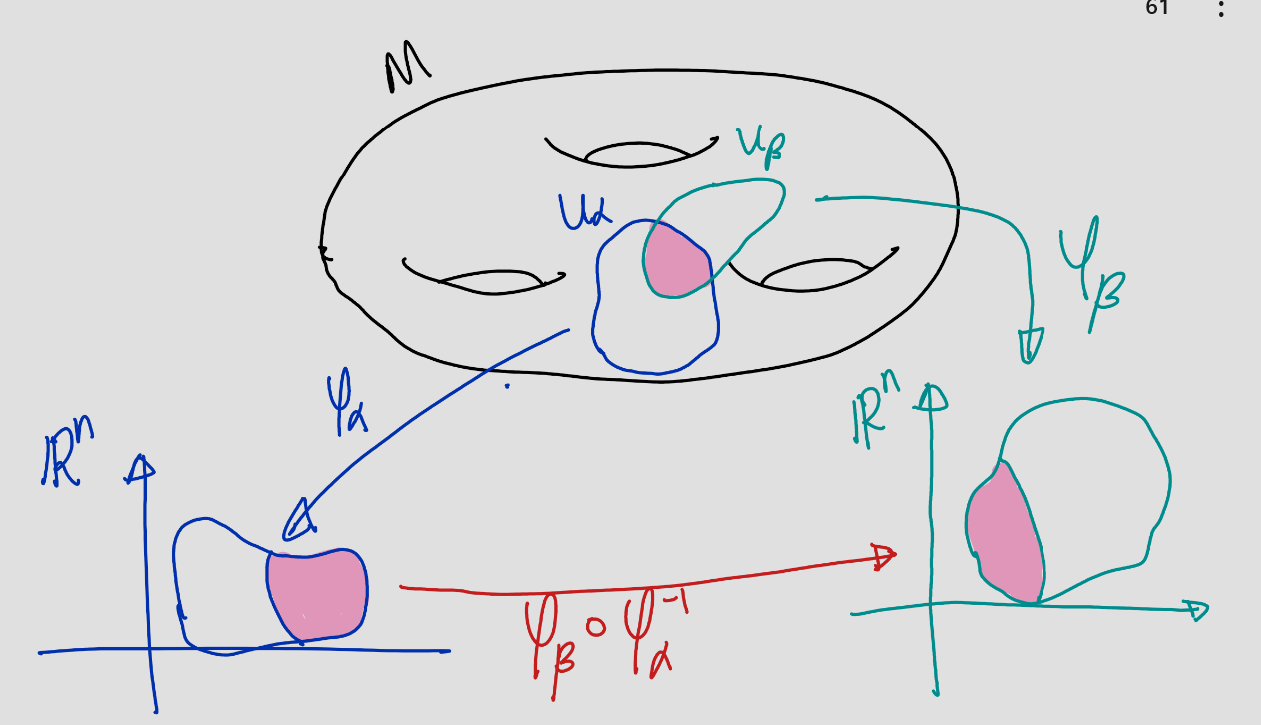

Theorem 2.1 Let \(M\) and \(A\) be sets. (Here \(A\) is the index set.) For all \(\alpha \in A\) assume that \(U_\alpha \subset M\) and \(V_\alpha \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) are subsets and that \(\varphi_\alpha : U_\alpha \rightarrow V_\alpha\) are bijective maps. Suppose the following holds:

\(\bigcup_{\alpha \in A} U_\alpha = M\),

\(\varphi_\alpha(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) is open for all \(\alpha, \beta \in A\) and

\(\varphi_\beta \circ \varphi_\alpha^{-1} : \varphi_\alpha(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \rightarrow \varphi_\beta(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta)\) is continuous for all \(\alpha, \beta \in A\).

Then \(M\) carries a unique topology for which all \(U_\alpha\) are open sets and all \(\varphi_\alpha\) are homeomorphisms.

Figure 2.5: \(~\)

Proof. We first show uniqueness:

Let \(\mathcal{T}\) be a topology on \(M\) containing the \(U_\alpha\) and such that the \(\varphi_\alpha\) are homeomorphisms.

If \(W \in \mathcal{T}\), then also \(W \cap U_\alpha \in \mathcal{T}\) and \(\varphi_\alpha(W \cap U_\alpha)\) is open for all \(\alpha \in A\).

Conversely, if \(W \subset M\) is a subset such that \(\varphi_\alpha(W \cap U_\alpha) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) is open for all \(\alpha \in A\), then

\(W \cap U_\alpha\) is also open in \(U_\alpha\) for all \(\alpha\). Since \(U_\alpha\) is open in \(M\), the set \(W \cap U_\alpha\) is open in \(M\).

By (i), \(W = \bigcup_{\alpha \in A} (W \cap U_\alpha)\) is also open in \(M\). We have shown that \(W \in \mathcal{T}\) if and only

if \(\varphi_\alpha(W \cap U_\alpha)\) is open in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) for all \(\alpha\),

\[\mathcal{T} = \{W \subset M :~ \varphi_\alpha(W \cap U_\alpha) \subset \mathbb{R}^n \text{ is open for all } \alpha \in A\}\].

Example 2.6 (Real-projective space.) We define the real-projective space by \[ M = \mathbb{RP}^n := \mathbb{P}(\mathbb{R}^{n+1}) := \{ L \subset \mathbb{R}^{n+1} \mid L \text{ is a one-dimensional vector subspace} \}. \]

We will use Theorem 2.1 to equip \(\mathbb{RP}^n\) with the structure of an \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold. Let’s set \[ A := \{ \text{affine-linear embeddings } \alpha : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^{n+1} \text{ with } 0 \notin \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n) \}. \]

Since \(\alpha\) is affine-linear, there exist a matrix \(B \in \text{M}_{(n+1) \times n} (\mathbb{R})\) and a vector \(c \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}\) such that \[ \alpha(x) = Bx + c \quad \text{for all } x \in \mathbb{R}^n. \]

As \(\alpha\) is an embedding, \(B\) has maximal rank, i.e., \(\text{rank}(B) = n\).

Consequently, \(\alpha(\mathbb{R}^n)\) is an affine-linear hyperplane. Let’s set \[ U_\alpha := \{ L \in \mathbb{RP}^n \mid L \cap \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n) \neq \varnothing \}. \]

For \(L \in U_\alpha\), the space \(L \cap \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n)\) consists of exactly one point, because otherwise we would have \(L \subset \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n)\) and hence \(0 \in \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n)\), which is a contradiction. Moreover, we have \[ \mathbb{RP}^n \setminus U_\alpha = \{ L \mid L \subset B(\mathbb{R}^n) \text{ is a one-dimensional subspace} \} \] where \(\alpha(x) = Bx + c\). For \(\alpha \in A\), let’s set \(V_\alpha := \mathbb{R}^n\) and define \[ \varphi_\alpha : U_\alpha \to V_\alpha, \quad \varphi_\alpha(L) := \alpha^{-1}(L \cap \alpha(\mathbb{R}^n)). \]

Then \(x_\alpha\) is a bijective map, and we have \[ \varphi_\alpha^{-1}(v) = R \cdot \alpha(v). \]