Chapter 2 Mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the branch of mathematics that studies the principles and methods of formal reasoning. It is based on symbolic languages that can express statements and arguments in a precise and unambiguous way.

2.1 Propositional logic & Logical operators

Propositional logic is a branch of mathematical logic that studies the logical relationships between propositions, which are statements that can be either true or false.

Definition 2.1 (Proposition (Statement)) Proposition (Statement) is a declarative sentence that is either true (T) or false (F), but not both.

Example 2.1

- A square has all its sides equal.

- Every Odd number is not divisible by 2.

- \(2 < 3\).

- \(\sqrt{2}\not\in \mathbb{Q}\).

- \(\mathbb{Z}\subseteq \mathbb{Q}\).

- The set \(\{10, 20, 30\}\) has three elements.

They are all true.

Example 2.2

- Every rectangle is a square.

- \((2 +4)^2 = 2^2 4^2\).

- \(\sqrt{2}\not\in\mathbb{R}\).

- \(\mathbb{R} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}\).

- \(\{10, 11, 12\} \cap \mathbb{N}=\emptyset\)

They are all false.

Remark. No sentence can be called a statement if

- It is a question.

- It is an order or request.

Example 2.3

- “How old are you?” cannot be assigned true or false (In fact, it is a question). So, it is not a statement.

- “Close the door” cannot be assigned u-ue or false (Infect, it is a command). So, it cannot be called a statement.

- “x is a natural number” depends on the value of x. So, it is not considered as a statement. However, often it’s referred to as an open statement.

Example 2.4

| NOT a statement | Statement |

|---|---|

| Add \(5\) to both sides. | Adding \(5\) to both sides of \(x − 5 = 37\) gives \(x = 42\). |

| \(\mathbb{Z}\) | \(42 \in \mathbb{Z}\) |

| \(42\) | 42 is not a number. |

| What is the solution of 2x = 84? | The solution of 2x = 84 is 42. |

2.2 Statements and Truth Values

Note: The truth (T) or falsity (F) of a statement is called its truth value.

Definition 2.2 A statement is called simple (or atomic) if it cannot be broken down into two or more statements.

Example 2.5

- \(2\) is an even number.

- A square has all its sides equal.

- \(7\) is an odd number.

Definition 2.3 A compound statement is one which is made up of two or more simple statements.

Example 2.6

- “\(7\) is both an odd and prime number” can be broken into two statements:

- “\(7\) is an odd number.”

- “\(7\) is a prime number.”

- So it is a compound statement.

Note: The simple statements which constitute a compound statement are called component statements.

2.3 More About Propositions

- We use letters to denote propositions, such as \(p, q, r, s\).

- The truth value of a proposition is denoted as:

- \(T\) for true

- \(F\) for false

Using these notations, we can form new (compound) propositions from known propositions.

This area of logic is known as propositional calculus or propositional logic.

Note: Calculus here refers to the manipulation or computation with symbols.

Example 2.7 Let: - \(p\): 7 is an odd number. - \(q\): 7 is a prime number. - \(r\): \(5 > 11\)

2.5 Logical Operators

Here are some important logical operators:

| Operator | Handle | Notation |

|---|---|---|

| Negation | not | \(\sim ,\neg\) |

| Conjunction | and | \(\land\) |

| Disjunction | or | \(\lor\) |

| Exclusive-or | xor | \(\oplus\) |

| Implication | implies | \(\rightarrow\) |

| Biconditional | if and only if (iff) | \(\leftrightarrow\) |

2.5.1 The Negation Operator (\(\sim,\neg\))

Given any proposition \(p\), we can form a new proposition:

“It is not true that \(p\)”, which is called the negation of \(p\).

Example 2.8 Let \(p\): “The number 2 is even.”

This statement is true.

Negation:

\(\sim p\): “It is not true that the number 2 is even.”

This new statement is false.

Definition 2.4 Let \(p\) be a proposition.

The statement “\(p\) is not the case” is another proposition called the negation of \(p\).

It is denoted \(\sim p\) and read as “not \(p\)”.

2.5.1.2 Alternate Expressions for Negation

Example 2.9 Let \(P\): “The number 2 is even.”

Then \(\sim P\) can be expressed as:

- “It’s not true that the number 2 is even.”

- “It is false that the number 2 is even.”

- “The number 2 is not even.”

Example 2.10 Let: - \(p\): “This book is interesting.”

Then the negation \(\lnot p\) (also written as \(\sim p\)) can be read as:

- “This book is not interesting.”

- “This book is uninteresting.”

- “It is not the case that this book is interesting.”

Note:

The symbol \(\lnot\) is called the negation operator.

It operates on a single logical proposition by complementing its truth value.

For this reason, it is also called the logical complement.

We now introduce logical operators that take two existing propositions and form a new compound proposition.

These operators are known as logical connectives.

2.5.2 The Conjunction Operator — “and”

The word “and” can be used to combine two statements to form a new statement.

Example 2.11 Let:

- \(P\): The number 2 is even.

- \(Q\): The number 3 is odd.

Then:

- \(R_1\): “The number 2 is even and the number 3 is odd.”

This is a true statement because both \(P\) and \(Q\) are true.

Example 2.12

- \(R_2\): “The number 1 is even and the number 3 is odd.” → False

- \(R_3\): “The number 2 is even and the number 4 is odd.” → False

- \(R_4\): “The number 3 is even and the number 2 is odd.” → False

2.5.3 The Disjunction Operator — “or”

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions.

The proposition “\(p\) or \(q\)” is called the disjunction of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted by \(p \lor q\).

- \(p \lor q\) is false only when both \(p\) and \(q\) are false.

- It is true otherwise.

2.5.3.1 Truth Table for Disjunction

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \lor q\) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

This is an inclusive or: true if either or both are true.

Example 2.13 Let: - \(S_1\): “The number 2 is even or the number 3 is odd.” → True - \(S_2\): “The number 1 is even or the number 3 is odd.” → True - \(S_3\): “The number 2 is even or the number 4 is odd.” → True - \(S_4\): “The number 3 is even or the number 2 is odd.” → False

2.5.4 The Exclusive OR Operator — “either or”

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions.

The exclusive or of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted \(p \oplus q\), is:

- True when exactly one of \(p\) or \(q\) is true.

- False when both are true or both are false.

2.5.4.1 Truth Table for Exclusive OR

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \oplus q\) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | F |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

“Either \(p\) or \(q\) is true, but not both.”

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions.

The exclusive or of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted \(p \oplus q\), is:

- True when exactly one of \(p\) or \(q\) is true.

- False when both are true or both are false.

Example 2.14 Let: - \(p\): This book is interesting. - \(q\): I am staying at home.

Then: - \(p \oplus q\): “Either this book is interesting, or I am staying at home, but not both.”

2.5.5 Implication Operator — “implies”

Let \(P\) and \(Q\) be propositions.

The implication “If \(P\), then \(Q\)” is written as \(P \Rightarrow Q\).

- This is called a conditional statement.

- It is false only when \(P\) is true and \(Q\) is false.

- Otherwise, it is true.

Example 2.15 Let:

- \(P\): The integer \(a\) is a multiple of 6.

- \(Q\): The integer \(a\) is divisible by 2.

Then:

- \(R\): “If \(a\) is a multiple of 6, then \(a\) is divisible by 2.”

This is a true statement.

In general, given any two statements \(P\) and \(Q\) whatsoever, we can form the new statement This is written symbolically as \(P \rightarrow Q\), which we read as or

Like the symbols \(\land\) (and) and \(\lor\) (or), the symbol \(\rightarrow\) has a very specific meaning. When we assert that the statement \(P \rightarrow Q\) is true, we mean that if \(P\) is true, then \(Q\) must also be true. In other words, the condition of \(P\) being true forces \(Q\) to be true.

A statement of the form \(P \rightarrow Q\) is called a because it means \(Q\) will be true under the condition that \(P\) is true.

Think of \(p \rightarrow q\) as a promise: whenever \(p\) is true, \(q\) will be true also.

There is only one way this promise can be broken—namely, if \(p\) is true but \(q\) is false.

Definition 2.5 Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The implication \(p \rightarrow q\) is:

- False when \(p\) is true and \(q\) is false

- True otherwise

In this implication: - \(p\) is called the hypothesis (or antecedent or premise) - \(q\) is called the conclusion (or consequence)

Example 2.16 If \(\underbrace{\text{a polygon is a triangle,}}_\text{hypothesis,p} then \underbrace{ \text{ the sum of its angle measures is 180°.}}_\text{conclusion,q}\)

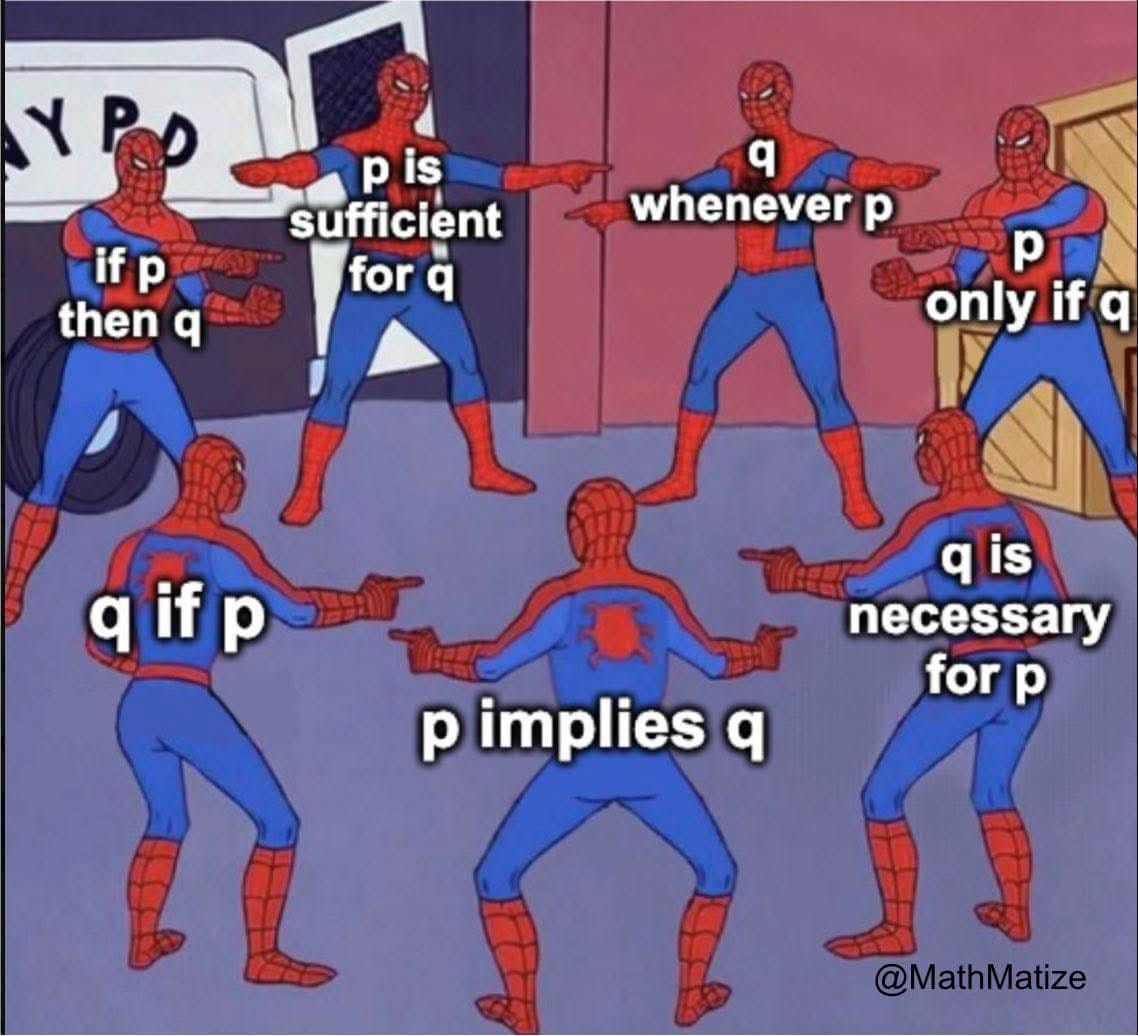

2.5.5.1 Ways to express an implication

- \(p \implies q\)

- “If \(p\), then \(q\)”

- “If \(p\), \(q\)”

- “\(p\) is sufficient for \(q\)”

- “\(q\) if \(p\)”

- “\(q\) when \(p\)”

- “\(p\) implies \(q\)”

- “\(p\) only if \(q\)”

- “\(q\) is necessary for \(p\)”

- “\(q\) follows from \(p\)”

2.5.5.2 Truth Table for \(p \implies q\)

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \implies q\) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

Remark.

- \(p \rightarrow q\) is false only when \(p\) is true and \(q\) is false.

- \(p \rightarrow q\) can be true even if \(p\) is false.

- The truth of \(p \rightarrow q\) does not require that either \(p\) or \(q\) is true.

Example 2.17 Consider the statement:

“Employee pays taxes only if his income is more than 3 million.”

Let:

- \(p\): Employee pays taxes

- \(q\): His income is more than 3 million

Symbolically:

\[ p \implies q \]

In other words:

- If employee pays taxes, then his income is more than 3 million.

- Employee’s income is more than 3 million, if he pays taxes.

Example 2.18 Consider the statement:

“If \(n^2\) is even, then \(n\) is even.”

Let:

- \(p\): \(n^2\) is even

- \(q\): \(n\) is even

Symbolically:

\[ p \implies q \]

2.5.6 Biconditional Logic: \(p \iff q\)

Definition 2.6 Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The biconditional \(p \iff q\) is:

- True when \(p\) and \(q\) have the same truth value

- False otherwise

Remark. The statement \(p \iff q\) is true precisely when both \(p \Rightarrow q\) and \(q \Rightarrow p\) are true.

This is why we say:

- “\(p\) if and only if \(q\)”

- \(p \iff q \equiv (p \Rightarrow q) \land (q \Rightarrow p)\)

2.5.6.1 Alternate phrasing

Not surprisingly, there are many ways of saying \(P \iff Q\) in English. The following constructions all mean \(P \iff Q\):

- \(P\) if and only if \(Q\).

- \(P\) is necessary and sufficient for \(Q\).

- For \(P\) it is necessary and suffcient that \(Q\).

- \(P\) is equivalent to \(Q\).

- If \(P\), then \(Q\), and conversely.

The first three of these just combine constructions from the previous section to express that\(P \implies Q\) and \(Q\implies P\). In the last one, the words “…and conversely” mean that in addition to “If \(P\), then \(Q\)” being true, the converse statement “*If \(Q\), then \(P\)” is also true.

2.5.6.2 Truth Table for \(p \iff q\)

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \iff q\) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \Rightarrow q\) | \(q \Rightarrow p\) | \((p \Rightarrow q) \land (q \Rightarrow p)\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | F | F |

| F | F | T | T | T |

Example 2.19

- “A number is divisible by 2 if and only if it is even.”

- “A number being even is a necessary and sufficient condition for it to be divisible by 2.”

2.5.7 Terminology

Let the compound statement be:

**“If** \(p\), then \(q\)” — symbolically written as \(p \rightarrow q\)

Components

- \(p\): Premise, Hypothesis, or Antecedent

- \(q\): Conclusion or Consequent

| Transformation | Symbolic Form | Verbal Form |

|---|---|---|

| Converse | \(q \rightarrow p\) | If \(q\), then \(p\) |

| Inverse | \(\neg p \rightarrow \neg q\) | If not \(p\), then not \(q\) |

| Contrapositive | \(\neg q \rightarrow \neg p\) | If not \(q\), then not \(p\) |

| Negation | \(p \land \neg q\) | \(p\) is true and \(q\) is false (i.e., the conditional fails) |

2.6 Truth Tables for Compound Propositions

To analyze compound propositions:

- Use separate columns for each sub-expression.

- Evaluate truth values for all combinations of truth values of the atomic propositions.

- The final column shows the truth value of the entire compound proposition.

Example 2.20

If a polygon is a triangle, then the sum of its angle measures is 180°

Let:

- \(p\): A polygon is a triangle

- \(q\): The sum of the angle measures of a polygon is \(180^\circ\)

Then the compound statement is:

- \(p \implies q\)

- Converse

The converse of a conditional statement \(p \implies q\) is \(q \implies p\)

Statement:

If the sum of the angle measures of a polygon is \(180^\circ\), then the polygon is a triangle.

Symbolically: \(q \implies p\)

- Inverse

The inverse of a conditional statement \(p \implies q\) is \(\neg p \implies \neg q\)

Statement:

If a polygon is not a triangle, then the sum of its angle measures is not \(180^\circ\).

Symbolically:

\(\neg p \rightarrow \neg q\)

- Contrapositive

The contrapositive of a conditional statement \(p \implies q\) is \(\neg q \implies \neg p\)

Statement:

If the sum of the angle measures of a polygon is not \(180^\circ\), then the polygon is not a triangle.

Symbolically: \(\neg q \implies \neg p\)

- Negation

The negation of a conditional statement \(p \implies q\) is \(p \land \neg q\)

Statement:

A polygon is a triangle and the sum of its angle measures is not \(180^\circ\).

Symbolically: \(p \land \neg q\)

2.7 Precedence of Logical Operations

To reduce parentheses in logical expressions, follow this precedence order:

| Operation | Symbol | Precedence |

|---|---|---|

| Negation | \(\neg\) | 1 |

| Conjunction | \(\land\) | 2 |

| Disjunction | \(\lor\) | 3 |

| Implication | \(\Rightarrow\) | 4 |

| Biconditional | \(\Leftrightarrow\) | 5 |

Example 2.21

\(p \lor q \land r\) means:\(p \lor (q \land r)\)

\((p \lor q) \land r\) requires parentheses to override precedence.

\(p \lor q \Rightarrow \neg r\) means: \((p \lor q) \Rightarrow (\neg r)\)

\(p \lor (q \Rightarrow \neg r)\) requires parentheses to clarify grouping.

Example 2.22 Parse the statement

\((\neg p) \Rightarrow (p \lor (q \land p))\)

This uses:

- Negation on \(p\)

- Conjunction \(q \land p\)

- Disjunction \(p \lor (q \land p)\)

- Implication from \(\neg p\) to the disjunction

2.8 Truth Tables and Logical Analysis

2.8.1 Constructing a Truth Table

To analyze a compound proposition:

Determine the number of atomic propositions:

If there are \(n\) propositions, the truth table will have \(2^n\) rows.List all combinations of truth values:

Fill the first \(n\) columns with all possible combinations of truth values for each proposition.Evaluate each sub-expression:

Add columns for intermediate steps and compute their truth values row by row.

Example 2.23 Construct a truth table for the compound proposition:

\[

(p \lor \neg q) \Rightarrow (p \land q)

\]

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(\neg q\) | \(p \lor \neg q\) | \(p \land q\) | \((p \lor \neg q) \Rightarrow (p \land q)\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | T | T | T |

| T | F | T | T | F | F |

| F | T | F | F | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | F | F |

Remark. To construct the truth table for a given proposition: 1 . Create a table with \(2^n\) rows if a compound proposition involves \(n\). propsitions. 2. Fill in the first \(n\) columns with all possible cobinations. 3. Determine and enter the truth value for each combination.

Example 2.24 For \(n=3\),

This table lists all possible combinations of truth values for three atomic propositions: \(p\), \(q\), and \(r\).

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \hline p & q & r \\ \hline T & T & T \\ F & T & T \\ T & F & T \\ F & F & T \\ T & T & F \\ F & T & F \\ T & F & F \\ F & F & F \\ \hline \end{array} \]

Exercise 2.1 Construct truth tables for the following compound propositions

\[ \neg (P \lor Q) \lor (\neg P) \]

\[ \neg (P \Rightarrow Q) \]

\[ P \lor (Q \Rightarrow R) \]

Exercise 2.2 Suppose the statement \(((P \land Q) \lor R) \Rightarrow (R \lor S)\) is false.

Find the truth values of \(P\), \(Q\), \(R\), and \(S\) without constructing a full truth table.

2.9 Tautologies and Contradictions

Definition 2.7

- A tautology is a compound proposition that is always true, regardless of the truth values of its components.

- A contradiction is a compound proposition that is always false.

- A contingency is a compound proposition that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction.

Example 2.25 Let \(p\): “This course is easy.”

- Contradiction:

“This course is easy and this course is not easy”

Expression: \(p \land \neg p\)

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \hline p & \neg p & p \land \neg p \\ \hline T & F & F \\ F & T & F \\ \hline \end{array} \]

- Tautology:

“This course is easy or this course is not easy”

Expression: \(p \lor \neg p\)

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|} \hline p & p \lor \neg p \\ \hline T & T \\ F & T \\ \hline \end{array} \]

2.10 Logical Equivalence

Definition 2.8 Two compound propositions \(p\) and \(q\) are logically equivalent if they yield the same truth values for all combinations of truth values of their components. Denoted as:

\[ p \equiv q \]

Remark.

- \(p \equiv q\) means that \(p \iff q\) is a tautology.

- The symbol \(\equiv\) is not a logical connective; it asserts that the biconditional \(p \iff q\) is always true.

2.10.1 Useful Logical Equivalences

These equivalences are foundational in propositional logic and are often used to simplify or transform logical expressions.

Double Negation

\[ \neg(\neg p) \equiv p \]De Morgan’s Law (Conjunction)

\[ \neg(p \land q) \equiv \neg p \lor \neg q \]De Morgan’s Law (Disjunction)

\[ \neg(p \lor q) \equiv \neg p \land \neg q \]Implication

\[ p \Rightarrow q \equiv \neg p \lor q \]Negation of Implication

\[ \neg(p \Rightarrow q) \equiv p \land \neg q \]

2.12 The Algebra of Propositions

2.12.1 Logical Laws and Their Equivalences

| Law Name | Disjunction-related Expression(s) | Conjunction-related Expression(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Idempotent Laws | \(p \lor p \equiv p\) | \(p \land p \equiv p\) |

| Associative Laws | \((p \lor q) \lor r \equiv p \lor (q \lor r)\) | \((p \land q) \land r \equiv p \land (q \land r)\) |

| Commutative Laws | \(p \lor q \equiv q \lor p\) | \(p \land q \equiv q \land p\) |

| Distributive Laws | \(p \lor (q \land r) \equiv (p \lor q) \land (p \lor r)\) | \(p \land (q \lor r) \equiv (p \land q) \lor (p \land r)\) |

| Identity Laws | \(p \lor F \equiv p\), \(p \lor T \equiv T\) | \(p \land F \equiv F\), \(p \land T \equiv p\) |

| Involution Law | — | \(\neg \neg p \equiv p\) |

| Complement Laws | \(\neg p \lor p \equiv T\) | \(\neg p \land p \equiv F\) |

| De Morgan’s Laws | \(\neg (p \land q) \equiv \neg p \lor \neg q\) | \(\neg (p \lor q) \equiv \neg p \land \neg q\) |

| Conditional Identities | \(p \Rightarrow q \equiv \neg p \lor q\) | \(p \Leftrightarrow q \equiv (p \Rightarrow q) \land (q \Rightarrow p)\) |

Example 2.26

Show that:

\[ p \land \neg (q \Rightarrow \neg r) \equiv p \land (q \land r) \]Show that:

\[ p \Leftrightarrow q \equiv \neg q \Leftrightarrow \neg p \]Using logically equivalent statements (without truth tables), show:

\[ \neg (\neg p \land q) \land (p \lor q) \equiv p \]

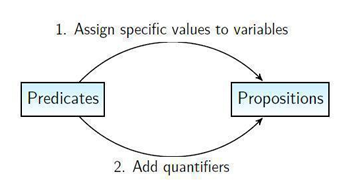

2.13 Predicate Logic and Quantifiers

Consider the following statements:

\[ x > 3, \quad x = y + 3, \quad x + y = z \]

The truth value of these statements has no meaning without specifying the values of \(x, y, z\).

However, we can make propositions out of such statements.

A predicate is a property that is true or false about the subject (in logic, we say “variable”) of a statement.

For example:

\[ \text{``} \quad \underbrace{x}_{\text{subject}} \quad \underbrace{\text{is greater than 3"}}_{\text{predicate}} \]

2.13.1 Predicates

A predicate is a declarative sentence whose truth value depends on one or more variables.

The statement: \[ x \text{ is greater than } 3 \]

has two parts:

- The predicate: “is greater than 3”

- The variable: \(x\)

We denote this statement by \(P(x)\), where:

- \(P\) is the predicate “is greater than 3”

- \(x\) is the variable

By assigning a value to \(x\), \(P(x)\) becomes a proposition with a definite truth value:

- \(P(5)\): “5 is greater than 3” → True

- \(P(2)\): “2 is greater than 3” → False

Note:

- A predicate is neither true nor false on its own.

- A predicate becomes a proposition when its variables are substituted with specific values.

- The domain (also called the universe or universe of discourse) of a predicate variable is the set of all values that may be substituted for the variable.

Definition 2.9 Let \(A\) be a nonempty set. An expression \(P(x)\) defined on \(A\) is called a predicate if:

\[ P(a) \text{ is either true or false for each } a \in A \]

That is, \(P(a)\) becomes a statement (i.e., a proposition with a definite truth value) whenever any element \(a \in A\) is substituted for the variable \(x\).

Example 2.27 (i) Let \(P(x): x^2 > 6\), where \(x \in \mathbb{N}\)

- \(P(1)\): \(1^2 = 1 \not> 6\) → False

- \(P(2)\): \(2^2 = 4 \not> 6\) → False

- For \(x \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(x \ne 1, x \ne 2\), \(P(x)\) is true.

(ii) Let \(P(x, y): x^2 + y^2 = 4\), where \(x, y \in \mathbb{R}\)

- \(P(0, 2)\): \(0^2 + 2^2 = 4\) → True

- \(P(1, 1)\): \(1^2 + 1^2 = 2\) → False

2.14 Quantifiers

A predicate becomes a proposition when we assign it fixed values. However, another way to convert a predicate into a proposition is by quantifying it.

Quantification expresses whether a predicate is true for:

- All values in the universe of discourse

- Some values in the universe of discourse

Definition 2.10 Quantifiers are words that refer to quantities such as “all” or “some.” They indicate how many elements in the domain satisfy a given predicate.

Two Types of Quantifiers

- Universal Quantifier

Symbol: \(\forall\)

Meaning: “For all” or “For every,” or “For each,” Example:

For every \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\), \(2n\) is even.

This can be expressed symbolically as:

\[ \forall n \in \mathbb{Z},\; 2n \text{ is even} \]

- Existential Quantifier

Symbol: \(\exists\)

Meaning: “There exists a” or “There is a.”

Example:

There exists an integer \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(n^2 = 2\).

This can be expressed symbolically as:

\[ \exists n \in \mathbb{Z},\; n^2 = 2 \]

2.14.1 Universal Quantifier \(\forall\)

Let \(p(x)\) be a predicate, where \(x \in D\).

Suppose the statement

> “For any \(x\) in a non-empty subset \(S \subseteq D\), \(p(x)\) is true”

is valid.

Then the expression

\[

\forall x \in S,\; p(x)

\]

is a proposition.

This means:

> “For every \(x\) in the subset \(S\), the predicate \(p(x)\) holds.”

Example 2.28 Let \(p(x)\): “\(x\) is even”

Let \(D = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10\}\)

Let \(S = \{2, 4, 6, 8, 10\} \subseteq D\)

Then: \[ \forall x \in S,\; p(x) \] is true, since all elements of \(S\) are even.

2.14.1.1 Notation

- \(\forall x\; P(x)\): Read as “for all \(x\), \(P(x)\)” or “for every \(x\), \(P(x)\)”

- \(\forall\): Universal quantifier

Definition 2.11 An element \(x\) for which \(P(x)\) is false is called a counterexample of \(\forall x P(x)\).

2.14.1.2 Other ways to say \(\forall\)

- All of…

- For each…

- Given any…

- For any…

- For arbitrary…

Example 2.29 Let \(P(x): x^2 > x\), where \(x\) is a real number.

Then “\(\forall x\, P(x)\)” in English means “for all \(x\), \(x^2 > x\)”, or we can say “for any \(x\), \(x^2 > x\)”, or in other words “given any \(x\), \(x^2 > x\)”.

An element \(x = \frac{1}{2}\), since \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2 = \frac{1}{4} < \frac{1}{2}\), is false. That is, \(P\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\) is false.

So, \(x = \frac{1}{2}\) is a counterexample to the statement “for all \(x\), \(x^2 > x\)”, where \(x\) is a real number.

Example 2.30 Consider the predicate \(|x| \geq 0\), where \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Let \(P(x): |x| \geq 0\).

Then, \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\, P(x)\) is true.

i.e., \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\, |x| \geq 0\).

Example 2.31 Consider the predicate \(x > \frac{1}{2}\), where \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Let \(P(x): x > \frac{1}{2}\).

Then \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\, P(x)\) is false, since for instance \(0 \in \mathbb{R}\), but \(P(0)\) is false.

i.e., \(\neg (\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\, P(x))\).

However, \(\forall x \in \mathbb{N},\, P(x)\) is true.

i.e., \(\forall x \in \mathbb{N},\, P(x)\).

2.14.2 The Existential Quantifier “\(\exists\)”

Let \(p(x)\) be a predicate, where \(x \in D\).

Suppose:

“There is \(x_0 \in S \subseteq D\), such that \(p(x_0)\)” is true.

Then:

“There is \(x_0 \in S \subseteq D\), such that \(p(x_0)\)” is a proposition.

We write this proposition as:

\[ \exists x_0 \in S,\ p(x_0) \]

Which means:

“There exists \(x_0 \in S\) such that \(p(x_0)\)” is true.

i.e.,

\[ \exists x_0 \in S,\ p(x_0) \]

2.14.2.2 Other ways to read \(\exists\):

- “There is an \(x\) such that \(P(x)\).”

- “There is at least one \(x\) such that \(P(x)\).”

- “For some \(x\), \(P(x)\).”

Example 2.32 Consider the predicate \(2x > 7\), where \(x \in \mathbb{N}\).

Let \(P(x): 2x > 7\).

When \(x \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(2x > 7\) is true (since \(10 > 7\)),

i.e., when \(x = 5\), \(x \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(P(5)\) is true.

Therefore,

\[ \exists x \in \mathbb{N},\ P(x) \text{ is true} \]

i.e.,

\[ \exists x \in \mathbb{N},\ 2x > 7 \]

Example 2.33 Consider the predicate \(x^2 > 1\), where \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Let \(A = \{0, 1, -1\}\) and define \(P(x): x^2 > 1\).

Then: - \(P(0)\) is false, - \(P(1)\) is false, - \(P(-1)\) is false.

Therefore,

\[ \exists x \in A,\ P(x) \]

is false,

i.e.,

\[ \neg (\exists x \in A,\ P(x)) \]

.

However,

\[ \exists x \in \mathbb{N},\ P(x) \]

is true,

since when \(x = 2\), \(x \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(P(2)\) is true.

i.e.,

\[ \exists x \in \mathbb{N},\ x^2 > 1. \]

Let \(p(x)\) be a predicate and \(D\) be the domain of \(x\).

An existential statement is a statement of the form:

\[ \exists x \in D,\ p(x) \]

- Forms:

- “There exists an \(x\) such that \(p(x)\)”

- “For some \(x\), \(p(x)\)”

- “We can find an \(x\) such that \(p(x)\)”

- “There is some \(x\) such that \(p(x)\)”

- “There is at least one \(x\) such that \(p(x)\)”

- The statement is true if \(p(x)\) is true for at least one \(x \in D\).

- The statement is false if \(p(x)\) is false for all \(x \in D\).

- A Counterproof to disprove an existential statement, one must show that \(p(x)\) is false for every \(x \in D\).

2.14.3 Quantifiers and Negation

Suppose \(A\) is a non-empty set, \(P(x)\) is a predicate where \(x \in A\), and \(B \subseteq A\) is a non-empty subset.

We consider the negations of quantified statements:

- Negation of a Universal Statement

\[ \neg (\forall x \in B,\ P(x)) \]

This means:

It is not the case that for every \(x \in B\), \(P(x)\) holds.

So, there exists some \(x \in B\) such that \(P(x)\) does not hold:

\[ \exists x \in B,\ \neg P(x) \]

- Negation of an Existential Statement

\[ \neg (\exists x \in B,\ P(x)) \]

This means:

It is not the case that there exists some \(x \in B\) such that \(P(x)\) holds.

So, for every \(x \in B\), \(P(x)\) does not hold:

\[ \forall x \in B,\ \neg P(x) \]

The following equivalences hold:

\[ \neg (\forall x \in B,\ P(x)) \equiv \exists x \in B,\ \neg P(x) \] \[ \neg (\exists x \in B,\ P(x)) \equiv \forall x \in B,\ \neg P(x) \]

\(\neg (\forall x \in D,\ p(x)) \equiv \exists x \in D,\ \neg p(x)\)

\(\neg (\exists x \in D,\ p(x)) \equiv \forall x \in D,\ \neg p(x)\)

The negation of a universal statement (“all are”) is logically equivalent to an existential statement (“there is at least one that is not”).

The negation of an existential statement (“some are”) is logically equivalent to a universal statement (“all are not”).

Example 2.34

\(\forall\) primes \(p\), \(p\) is odd

Negation: \(\exists\) prime \(p\), \(p\) is even\(\exists\) triangle \(T\), the sum of angles of \(T\) equals \(200^\circ\)

Negation: \(\forall\) triangles \(T\), the sum of angles of \(T\) does not equal \(200^\circ\)

2.14.3.1 Truth Value of Quantified Statements

| Statement | When True | When False |

|---|---|---|

| \(\forall x \in D,\ P(x)\) | \(P(x)\) is true for every \(x \in D\) | There exists at least one \(x \in D\) such that \(P(x)\) is false |

| \(\exists x \in D,\ P(x)\) | There exists at least one \(x \in D\) such that \(P(x)\) is true | \(P(x)\) is false for every \(x \in D\) |

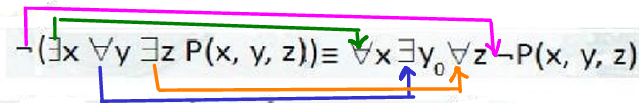

Example 2.35 We are given the logical equivalence: \[ \neg (\exists x\ \forall y\ \exists z\ P(x, y, z)) \equiv \forall x\ \exists y\ \forall z\ \neg P(x, y, z) \]

Note:

Logical operations from propositional logic — such as \(\neg\), \(\land\), \(\lor\), \(\Rightarrow\), \(\Leftrightarrow\) —

can also be applied to quantified statements.

Here is a clean transcription of the image content, showing only the questions and definitions without any answers or reformulations:

2.14.4 Negation of Quantification

Given a quantified statement of the form:

\[ \neg(\forall x \in D,\, P(x) \land Q(x)) \]

Apply logical transformations to express its equivalent forms.

2.14.4.1 Conditional Quantification

Consider the conditional quantification:

\[ \forall x \in D,\, P(x) \Rightarrow Q(x) \]

Define the following related forms:

Converse: \(\forall x \in D,\, Q(x) \Rightarrow P(x)\)

Contrapositive: \(\forall x \in D,\, \neg Q(x) \Rightarrow \neg P(x)\)

Inverse:\(\forall x \in D,\, \neg P(x) \Rightarrow \neg Q(x)\)

Note: : A conditional proposition is logically equivalnce to its contrapositive.

\[ \forall x \in D, P(x) \implies Q(x)\equiv \forall x\in D, \neg Q(x) \implies \neg P(x) \]

2.14.5 Negation of Conditional Quantification

\[\begin{align} \neg (\forall x \in D, P(x) \implies Q(x)) &\equiv \exists x_0 \in D \neg (P(x_0) \implies Q(x_0))\\ & \equiv \exists x_0 \in D P(x_0) \land \neg Q(x_0) \end{align}\]

Example 2.36 Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

\(x = 1\) is a sufficient condition for \(x^2 = 1\)

i.e., \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\ x = 1 \Rightarrow x^2 = 1\)\(x^2 = 1\) is a necessary condition for \(x = 1\)

i.e., \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\ x^2 \neq 1 \Rightarrow x \neq 1\)\(x = 1\) only if \(x^2 = 1\)

i.e., \(\forall x \in \mathbb{R},\ x^2 \neq 1 \Rightarrow x \neq 1\)

Example 2.37 Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Statement: \(\forall x,\ x > 10 \Rightarrow x^2 > 100\)

Negation: \(\exists x \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(x > 10\) and \(x^2 \leq 100\)

Example 2.38 Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Statement:

If \(x > 1\), then \(x^2 > 1\)

Define:

\(P(x): x > 1\)

\(Q(x): x^2 > 1\)

Symbolic form:

\[ \forall x \in \mathbb{R},\ P(x) \Rightarrow Q(x) \]

Negation:

\[ \exists x_0 \in \mathbb{R},\ P(x_0) \land \neg Q(x_0) \]

i.e.,

\[ x_0 > 1 \quad \text{and} \quad x_0^2 \leq 1 \]